R.I.P. GOP

Born of a righteous conviction that no person should be enslaved, the Republican Party died this week, a victim of its leaders’ lust for power and abandonment of the Union which Lincoln fought to save. At its zenith, the GOP advanced a freedom agenda derived from the ideals of the American experience and the European enlightenment. A commitment to free labor, free markets, free trade, and free institutions provided the philosophical underpinnings of Republican governments. By the time of its death, however, the Republican Party had devolved into an openly authoritarian party.

Between 1992 and 2020, the GOP won only one popular vote for president, but controlled the White House for 12 of those 28 years. Over that period, the party came to embrace decidedly un-democratic solutions to their electoral weakness: gerrymandering congressional districts, adopting voter suppression, welcoming assistance from hostile foreign governments in elections, and, most recently, undermining the U.S. postal service in a bald-faced effort to prohibit voting by mail in the midst of a global pandemic that has already taken the lives of 180,000 citizens, so far.

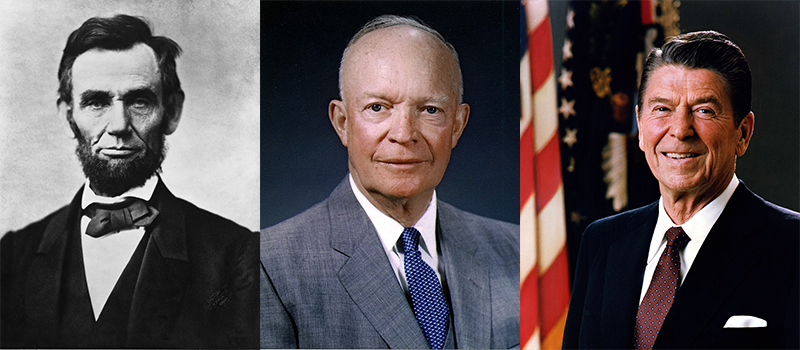

The life of any political party is intertwined with the accomplishments of its greatest politicians, its accomplishments not the fruit of populism but of the power of ideas and the political skills of its leaders. Here, the Republican party can lay claim to a proud history.

The Republican Party traces its roots to 1854 when a coalition of former Whigs and Free Soilers organized their opposition to the dominant Democratic Party. Their principal, animating impetus was opposition to the expansion of territories in the growing United States where slavery was legal. This was the decade of the Missouri Compromise, of bleeding Kansas, of John Brown’s raid. National politics seemed woefully incapable of dealing with the issue of slavery. Two years after the party’s establishment, it’s first presidential candidate John C. Fremont won 11 of the 16 Northern states in the Union. Then in 1860, Abraham Lincoln won election to the presidency of the United States of America. The civil war that followed tested the republic in ways that linger to this day. Still, Lincoln’s steadfast defense of the Union, his wartime emancipation of Southern slaves, his support for the 13th amendment prohibiting slavery in the United States, and, tragically, his martyrdom, place him in the pantheon of American presidents. If Lincoln’s presidency was the only service Republicans had done, then their status among American political parties would be secure.

But that’s not the end of the legacy of the Republican party.

In the middle of the 20th century, the United States and, indeed, the free world, faced a new, existential threat. Dwight Eisenhower rose to political prominence as commander of the allied armies fighting fascism and Nazis in Europe. Upon entering American domestic politics, he focused the country on a long-strategy to prevail in “cold war.” It was Eisenhower’s administration that linked ends and means—the stuff of strategy—with an incisive view of the Soviet threat and its internal weaknesses. The strategy Eisenhower adopted sought to build American and Western strength while exploiting Soviet weaknesses and Eastern bloc divisions. The broad outlines initiated by Truman were formalized by Eisenhower and guided American presidents through the end of the Cold War.

The end of the Cold War had as much to do with Soviet leadership as it did with American policies. But when a young Mikhail Gorbachev and a young Eduard Shevardnadze confided in one another—years before they rose to the roles of premier and foreign minister, respectively—that the Soviet system was failing and much in-need of reform, the long-twilight struggle organized by Eisenhower raced to a conclusion. Where Republican President Ronald Reagan provided the inspirational leadership of a nation committed to freedom around the world, President George H. W. Bush, another Republican, managed the end of the Cold War, the collapse of the Warsaw Pact, and the demise of the Soviet Union with masterful diplomacy.

No life examined is ever flawless. The GOP’s response to the Great Depression left far too many Americans hungry, without shelter, and without work. While Democrats and Republicans supported the 2003 march to war in Iraq, the administration of President George W. Bush will own forever the decision to invade that country.

But it’s the transformation of the Republican Party between 2016 and 2020 from the Grand Ol’ Party to the party of Trump that lies so fundamentally outside the boundaries of American political norms. In its final years, the party dismissed the high-minded ideals of Lincoln, Eisenhower, Reagan and both Bushes. Instead, by the time of its death, the GOP looked like a party committed to holding on to power at all costs. It embraced well-documented voter suppression efforts. Its standard bearer repeatedly sought foreign intervention to support his election and re-election. Cynicism replaced ideals and truth was drowned in a torrent of lies on everything from the president’s extra-marital affairs to proper treatments for a pandemic virus. Cronyism replaced competence and the meritocracy of public service was replaced by those who seek the favor of the president, who stroke his ego, and who deliver the news he wants to hear.

The final, fatal blow for the party came this week when it announced it would not issue a party platform for the 2020 election. Devoid of principles other than fealty to the president, the party issued a press release that said, feebly, that had it issued a platform, it “would have undoubtedly unanimously agreed to reassert the Party’s strong support for President Donald Trump and his administration.”

Political parties emerged to give coherence to the ideas that candidates could mobilize around. They served—in the era before instant communication—to provide an infrastructure for the dissemination of those ideas. While modern technology makes it easier to communicate, the ideas we communicate still matter. In failing to articulate a platform other than adulation for the leader, the Republican party has revealed itself to be nothing more than an authoritarian party.

Authoritarianism is inconsistent with republican government, with democracy, with the long history of American governance and our role in the world—and that’s why the Republican Party, as a governing party in these United States of America, is dead. The only remaining question is whether its illness spread deeply into the free-institutions of our nation and whether Lincoln’s government of, by and for the people shall perish, too, from this Earth.