Iraq: Ten Years Later

There is no decision more grave than a decision to go to war. History has taught us, time and again, that once unleashed, the dogs of war have no master. Unintended consequences abound. And no plan survives first contact with the enemy.

As we approach the ten year anniversary of the war in Iraq, those truisms—almost cliché—have to be uppermost in our minds when we talk about that war.

The Iraq war raised fundamental questions about the appropriate use and purpose of American power. Its architects belong to a school of thinkers called “neo-conservative.” They believed that the combination of American military power and its benign intent would enable the United States to transform the politics of the Middle East with a lightening strike in Iraq.

They seized on the public’s fear after 9/11 and took us to war. A decade later, it’s appropriate to think about the lessons the Iraq war holds for the exercise of American power in the future.

And today, on the tenth anniversary of the start of the war, there are three ideas uppermost in my mind—about history, about judgments, and about the proper use of American power. In the end, any reckoning often involves painful truths. And the Iraq War has plenty for folks left-right-and-center.

Idea 1: Modern Iraq has never known political stability

After World War I and the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, the League of Nations granted a mandate to Britain in Mesopotamia. British diplomats like Gertrude Bell—famous for traveling across the desert and living amongst the Bedouins—devised a state whose boundaries and structure demonstrated little regard for historic animosities.

In the 35 years from 1933 to the Ba’th seizure of power in 1968, Iraq suffered from 25 incidents of extra-constitutional disturbances: coups, attempted coups, uprisings, sectarian and political hostilities, and so forth. 25 incidents in 35 years—that’s an average of one every 17 months. If we expand the calendar to Saddam’s rise to prominence in 1978, the incidents average one every 18 months.

Throughout this period, carrying on the tradition dating to the Ottoman experience, the Sunnis in Iraq dominated the bureaucracy and the military. The record of political violence is almost always of one group, political or sectarian, trying to gain advantage over others—or of the Kurds trying to break-free.

This historical experience created a tremendously violent political tradition that continues to manifest itself today.

Idea 2: George H.W. Bush and the Exercise of Prudence

During the presidency of George H. W. Bush, comedian Dana Carvey skewered the president regularly on Saturday Night Live. “Nah gonna do it,” Carvey would say, his hand rigidly gesturing, his voice contorted to mimic Bush’s, “Would’n’ be prudent at this juncture.”

But it was his father’s prudence and good judgment that President George W. Bush was so sorely missing.

On September 2, 1990, Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait. The United States, under the leadership of President George H. W. Bush marshaled a mighty international coalition and expelled the invader the following spring.

Most importantly, the first President Bush never sought regime change. He and his national security advisor, Brent Scowcroft, detailed the thinking in 1998:

Trying to eliminate Saddam, extending the ground war into an occupation of Iraq, would have violated our guideline about not changing objectives in midstream, engaging in “mission creep” and would have incurred incalculable human and political costs. Apprehending him was probably impossible. We had been unable to find Noriega in Panama, which we knew intimately. We would have been forced to occupy Baghdad and, in effect, rule Iraq. The coalition would instantly have collapsed, the Arabs deserting it in anger and other allies pulling out as well. Under those circumstances, there was no viable “exit strategy” we could see, violating another of our principles. Furthermore, we had been self-consciously trying to set a pattern for handling aggression in the post-Cold War world. Going in and occupying Iraq, thus unilaterally exceeding the United Nations’ mandate, would have destroyed the precedent of international response to aggression that we hoped to establish. Had we gone the invasion route, the United States could conceivably still be an occupying power in a bitterly hostile land. It would have been a dramatically different—and perhaps barren—outcome.”

–George H. W. Bush and Brent Scowcroft, A World Transformed, 1998.

Idea 3: The Neocons and the Aggressive Use of American Power

In the aftermath of the 1991 conflict, the Bush administration built a robust containment regime in the Persian Gulf region. No-Fly Zones, punitive sanctions, and arms inspections limited Iraq’s sovereignty and contained the threat from Baghdad.

That’s not to say this was anything like the containment strategy in place against the Soviet Union in the Cold War. Military strikes were common—either against air-defense systems in the no-fly zones, or in larger strikes following the attempted assassination of President George H. W. Bush in Kuwait or Operation Desert Fox.

By the end of the 1990s, a decade long strategy of containment had slowly strangled the Iraqi regime of Saddam Hussein. His weapons of mass destruction programs were suspended because of U.N. Sanctions. But with the ejection of U.N. inspectors after Desert Fox, the United States was effectively flying blind about Saddam’s weapons programs.

Political leaders in both parties began to worry in public about the consequences of this intelligence gap. They worried that the containment strategy was buckling under the pressure of black-market smuggling of Iraqi oil and abuses of the UN’s Oil-for-Food program.

Into this environment came a cabal that believed the United States had been too timid in the first Gulf War, who believed that American power was being frittered away in the desert, and that our strategy was failing. They organized in the Project for a New American Century and their 1998 letter to President Clinton is widely recognized as the beginning of the campaign to topple Saddam that resulted in Operation Iraqi Freedom.

But in the neocon manifesto, there echoes the autopsy of another war:

There is a final result of Vietnam policy I would cite that holds potential danger for the future of American foreign policy: the rise of a new breed of American ideologues who see Vietnam as the ultimate test of their doctrine. I have in mind those men in Washington who have given a new life to the missionary impulse in American foreign relations: who believe that this nation, in this era, has received a threefold endowment that can transform the world. As they see it, that endowment is composed of, first, our unsurpassed military might; second, our clear technological supremacy; and third, our allegedly invincible benevolence (our “altruism,” our affluence, our lack of territorial aspirations). Together, it is argued, this threefold endowment provides us with the opportunity and the obligation to ease the nations of the earth toward modernization and stability: toward a fullfledged Pax Americana Technocratica. In reaching toward this goal, Vietnam is viewed as the last and crucial test. Once we have succeeded there, the road ahead is clear. In a sense, these men are our counterpart to the visionaries of Communism’s radical left: they are technocracy’s own Maoists. They do not govern Washington today. But their doctrine rides high.

—James C. Thomson, “How Could Vietnam Happen: An Autopsy,” The Atlantic, April 1, 1968.

Why It Matters

Learning the right lessons from Iraq matters for so many reasons. But the starkest reason to study the conflict is found in the lives lost, the bodies and minds scarred, the dead and the wounded.

The war in Iraq cost the United States and its coalition partners the lives of 4,804 service members. U.S. casualties alone were 4,488. 32,221 Americans were wounded in action. And untold thousands more have been scarred with the invisible wounds that come with war—post-traumatic stress and other emotional wounds.

We have an obligation to those who wear the uniform to get this right. And we have an obligation to those who will wear the uniform in the future to learn lessons from this war so that its mistakes are never again repeated.

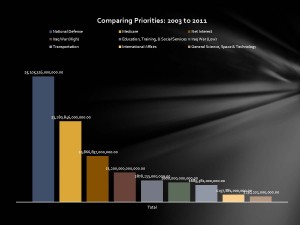

Financially, estimates vary, but a good range for the actual cost of the war in Iraq is $800 billion to more than $1 trillion—between March 2003 and December 2011. Put another way, Iraq was more costly than World War I, the War in Korea and the Vietnam War and cost as much, by some estimates, as Korea and Vietnam combined.

Worse still, we didn’t pay for the war. We financed it on the backs of our children and grand-children.

Lessons on the Use of American Power

Iraq was a mistake, a colossal misjudgment, and ten years after the start of the war, the implications are clear:

- You can accomplish great things through diplomacy, political strategy, and military readiness. Saddam was contained. He did not threaten his neighbors. He was not actively pursuing WMD.

- Challenges to American interests are not always best met by the direct, unilateral application of American power. Simply compare the costs of Iraq with the benefits to date.

- There remains an appropriate role for American military force in the exercise of American power. Military power gives credibility and heft to political and diplomatic initiatives.

- The value of international institutions is reaffirmed. In the Autumn of 2002, the unified voice of the United Nations served to put UN inspectors back into Iraq. They found nothing. The United States acted before they could establish that Iraq had nothing to hide except its own weakness. If we didn’t have a United Nations, we’d want one.

- American political leaders, military leaders, civilians and service members need to be better versed in history, languages, and cultures of the places from where challenges are likely to emanate. There is both strategic and tactical value in understanding the context in which we find ourselves exercising power.

- Congress has been broken for a long time. There was no real challenge to the President’s prerogative to wage a war of choice in Iraq. There was no sustained inquiry and there was tragically little oversight after the war began.