Heroes

Growing up, I watched more than my fair share of television. One of my favorite diversions was a show I caught in syndicated re-runs long after it was out of production. “Baa Baa Black Sheep” was a fictional account of Gregory “Pappy” Boyington, the Marine Corps’ ace of aces in the Second World War, and his squadron, VMF-214—The Black Sheep. The show got virtually everything wrong in the history of the squadron, but it sparked my imagination. Long before the internet, I spent hours in my local library looking for books and articles about the real Pappy Boyington. When I found his autobiography, I was stunned to learn that Boyington recalled wistfully his time in a Japanese POW camp because it was one of the few periods in his life that he wasn’t able to drink. The self-loathing that fueled much of his risk taking was summed up, famously, when he wrote, “Show me a hero, and I’ll show you a bum.”

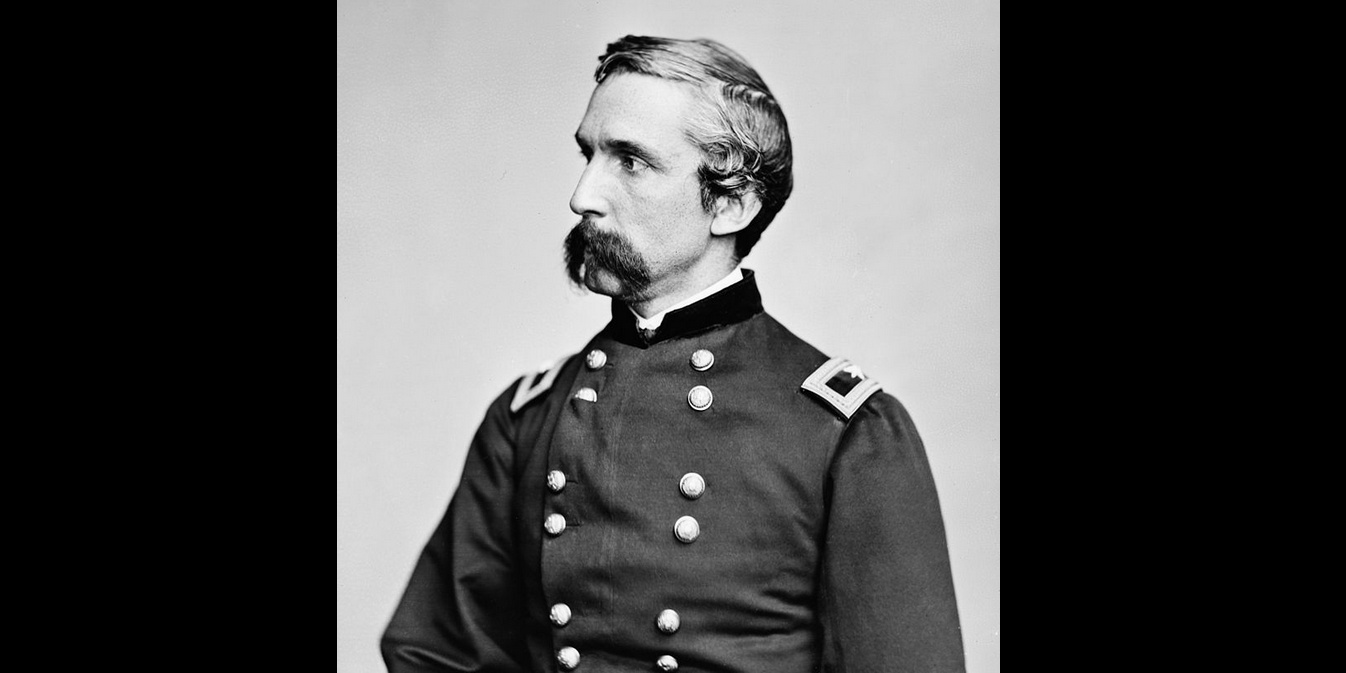

I had other heroes, too. One that I still carry today is Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain—the commanding officer of the 20th Maine at the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863. Sent to defend the extreme left-flank of the Union line on Little Round Top, the 20th Maine held off repeated Confederate assaults until their ammunition ran low. Then, Chamberlain, improvising a maneuver similar to the pivot of a gate on a hinge, ordered his men to fix bayonets and sweep down the hill, chasing Confederate forces in front of them as they ran. With profound physical courage and the ability to keep his wits in the face of incredible danger, Chamberlain saved the Union line at Gettysburg. Less than a year later, at Petersburg, he would be severely wounded, but recovered and was chosen by Ulysses S. Grant as the Union Officer to receive the Confederate surrender at Appomattox Courthouse. In that moment of triumph, Chamberlain called Union troops to attention as one last martial salute to their foes—a move heralded by some and criticized by others as the most gracious conceivable act of battlefield respect.

Later, I learned more about Chamberlain: he wasn’t always a war hero, he wasn’t even a military man. He was a professor of rhetoric at Bowdoin College who volunteered to serve the Union cause because he thought it was just and that for the Union to prevail, men in the North would have to leave positions of comfort. He was an idealist willing to put his life on the line for those ideals.

Taken at face value, there’s not a lot of reason to see anything similar in Boyington and Chamberlain. After the Civil War, Chamberlain would become President of Bowdoin College and Governor of Maine. After World War II, Boyington struggled to hold down odd jobs, including a stint as a professional wrestling referee. With some age and perspective, I came to appreciate that if we can get past hero worship—and its opposite, vilification—then we can see that the people in the news are not really any different than the rest of us. They have jobs to do, but they are people: flawed, wonderful, cynical, idealistic, talented, mediocre, sober or drunk, who find themselves in the eye of history.

That was certainly the case for Boyington and Chamberlain. But it’s true, now, of others, too, including the steady stream of witnesses appearing before the Congressional impeachment inquiry: people like Lt. Colonel Alexander Vindman, NSC staffers Tim Morrison and Fiona Hill, and Ambassador Robert Taylor.

Ultimately, the history of this era will be written by the quiet Americans who prize public service as a good they can perform for the benefit of all, not the benefit of one; who take their oath to the Constitution seriously; and who speak truth to power—even at great professional risk. But that’s true of every era. Heroes are normal people in extraordinary circumstances—whether they are an NSC staffer who hears something inappropriate in a presidential phone call or if they are an Army commando raiding a compound in Northern Syria. None of those Americans were born heroes, but like Chamberlain and even Boyington, they all prize something greater than themselves: the Constitution, the rule of law, and the idea that there are some things worth fighting for.